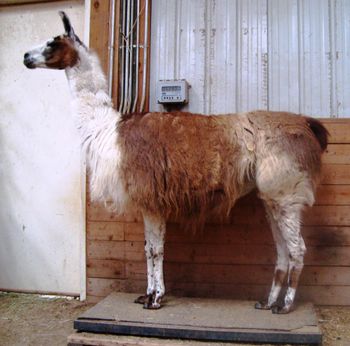

This is a photo of Speckles son of Freckles and Sir Alberto he was gelded at age 6 and had dropped by age 10

Should you geld your Pack Llamas???

Don’t automatically geld your intended packers, this is an irreversible action and deserves careful consideration. It has generally been accepted males not to be used for breeding should be gelded. Conventional wisdom used to believe intact males could neither live together in a herd, nor work together on the trail. That was a whole lot of bunk!! This is not to say there aren’t some parameters that need to be considered. (More about this later) However there can be a huge downside to gelding your packers, which is certainly the case in NW Wyoming. We also place llamas with people from other areas of the country that need to give their gelded packers early retirement due to fallen pasterns, (the common term used to describe; down in the fetlock, or hyperextension of the fetlock, or weak pastern) I acknowledge this problem is not universal, but it is widespread and serious, so why take the chance if you don’t have to. We all want our partners on the trail to be with us as long as possible, and it is a sad day when we have to leave them home.

In the past it was convenient and common practice to geld surplus males as early as 4 to 6 months of age. It was then discovered this early gelding caused the growth plates to remain open longer and resulted in llamas growing taller than their structure could support. This is the origin of the myth that tall llamas can’t work and will break down. These poor llamas along with others that didn’t meet the breeder’s goals (anything but packing) were marketed as packers. Of course llamas being the wonderful creatures that they are, tried to do what they were asked, but the majority were physically incapable of extensive packing. Now it is recommended not to geld until the animals are full grown. This solved the growth problem, and this was the practice we followed. We only gelded the animals that were a little too aggressive in their group (12 to 20 intact males), never prior to 3 years old and up to 7 years old. It only took a few years for us to realize the geldings were starting to break down and their intact counterparts were going strong. We completely stopped gelding a number of years ago and every male we gelded ended up in early retirement, prior to 15 years of age and some at 12. With only a couple of exceptions the intact males are capable of heavy duty work into their late teens. Arthritis, probably something to do with long cold (lots of -30 f and beyond) winters and many years on the trail, pretty much sets the time for the “gold watch”, but most continue to remain up on their pasterns their entire lives.

There are some considerations when keeping intact males, the main issue is having enough room for them to settle a dispute when playing ends up with someone getting mad. One acre per llama up to 10 acres is a good rule of thumb. They also need plenty of room at the feeding areas, not too different from dominant females. Spending time on the trail together absolutely re-enforces their cohesiveness as a herd. The whole situation is much simpler if there are no females around. Age is important, keep them in their own age groups until age 4.The boys go through what we refer to as the terrible two’s, the equivalent of adolescence in human teenagers. They seem to constantly want to wrestle and chase each other. As they gain size and strength it looks scary but we feel it really helps to develop their muscle. Their chests and thighs begin to feel like they are made of steel. This starts at age 2 to 2 ½ and lasts until 4 but some individuals take it to 6. If they are spending time on the trail together age 4 is the norm. Even though they are approaching full grown and look tough as nails, they are high school kids and you don’t put them in the NFL, in this case mixed with 4 year and older males. You also need to really keep on top of their fighting teeth. It would be nice if they all erupted at once, or at least if they all came out at the same time in each llama, but this doesn’t happen so it is usually several episodes of trimming.

Don’t panic at the occasional dust ups, the speed and power they display is awesome, but fortunately serious injuries are extremely rare, and after the fight they are best buddies again.

Adendum: These considerations should have been included in original piece

It seems probable that pastern strength is affected by a combination of things; genetics, weight, nutrition overall health, but an important component is obviously hormones. I kind of think sometimes we are on the edge of some deficiency, copper, boron, whatever, and the presence or lack of hormones tips the balance. Genetics could be playing two roles, structural weakness where nothing makes a difference, but also the ability to assimilate or thrive on diminished levels of some key nutrient or combo of nutrients. This could explain different outcomes in different parts of the country. While we don’t all agree on the importance of natural hormones, I think most of us agree grossly overweight llamas are almost certain to drop. Plenty of exercise is important, but carrying loads too heavy for the body structure will also cause a breakdown. A loaded llama should show no basic difference in their stride than when they aren’t carrying a load. Forget the old "percent of body weight" theory.

One last very important point: VIRTUALLY NONE OF OUR FEMALES HAVE EXPERIENCED FALLEN PASTERNS!! There has been only one or two exceptions to this, however the last few weeks prior to their natural demise some will start to fall, as is true with some of the intact males. I take it as a signal the end is near and the entire body is starting to break down and keep a close watch to be sure they don't stop eating or drinking or suffer.

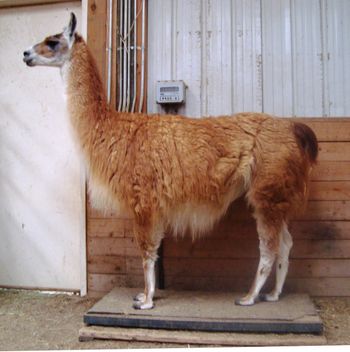

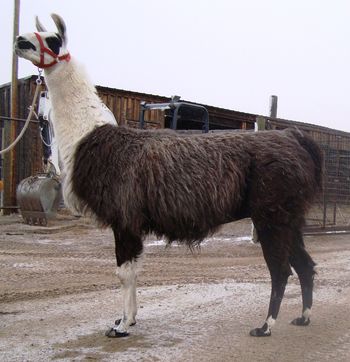

It seems appropriate to include photos of our remaining females and our last two intact male packers with thousands of hard miles under their saddles we regret not documenting all of our animals in their old age to emphasize the effect of gelding in our experiences.